On December 13th Movement Alliance Project (MAP), formally known as Media Mobilizing Project, held their annual Community Building Dinner. It offered a time for the city’s activist community to take a break from their various battles with Philadelphia’s establishment and rejoice over the year’s past accomplishments. It was an exciting evening, filled with the likes of community organizers and allied politicians. Young kids ran the halls while adults struck a pose in the photo booth. However, as the room stirred with activity one man beside me sat quietly taking it all in.

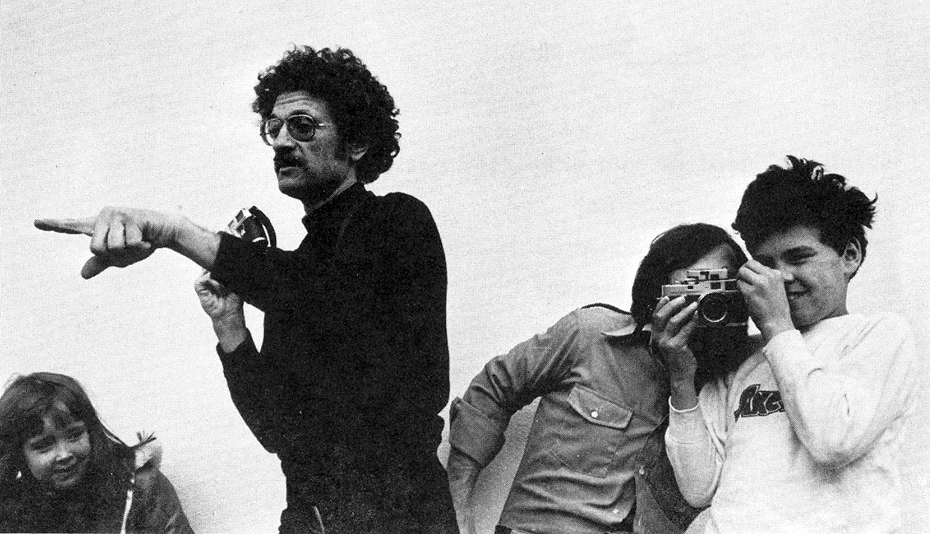

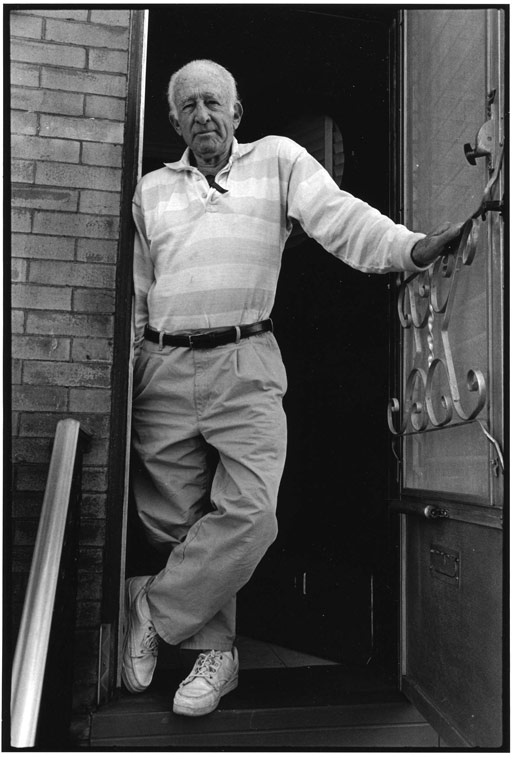

His name is Harvey Finkle, the renown photographer covering Philadelphia social movements and issues for the last half century. Finkle’s presence didn’t go unknown, in fact he was quite popular. As we sat and talked guest after guest made sure to venture to our table to greet Finkle; in a manner of paying respect, rather than gesturing a simple hello. Finkle’s work and achievements sprawls five decades and is practically endless. His work illuminates issues left in the dark, while simultaneously telling the historical story of Philadelphia and areas abroad. Recently I sat down with Finkle in his Sansom Street studio in Center City to learn more about his story and to highlight the incredible work he’s produced.

At 85 years old Finkle doesn’t seem to miss a beat. Without hesitation he recalls decades old moments he experienced while shooting demonstrations or protests. A native of Philadelphia, Finkle has lived almost his entire life in the city of brotherly love. He grew up in Oxford Circle and attended Central High School. “I didn’t like school that much” said Finkle “It was too containing”. School came second to Finkle during his early years. He described his love for jazz music and how him and his friends in the early 50’s would often attend jazz clubs. One in particular he mentioned was the Blue Note, a club that was located on 15th and Ridge in Fairmount. “We were 15 or 16, but it didn’t matter. You’d give the bouncer a buck and you were good to go in” he said. “I loved it; I could sit there for hours”. Years later, Finkle found that his interest in jazz translated into his photography. “Street photography is like jazz; you have to improvise”. Most of Finkle’s work is dependent on capturing a moment in real time. Just as jazz musicians adjust to the atmosphere of their audience, Finkle must instinctively adjust to the situation of his subjects.

What struck me most about Finkle is that he didn’t grow up with an interest in photography, let alone art in particular. In fact, photojournalism is his second career. After serving two years in the army, Harvey graduated from Temple University and began a career in social work. He began his career as a case worker for the city’s welfare department and later transition to work around incidents of reported child abuse. Similarly to his love for jazz, Finkle found that his time as a social worker assisted him in his career as a photojournalist. “This was good training for me to be a photographer” he said, “Because you’re in a home where people don’t want you there” He continued his career in social work by helping to establish services for Pennsylvania’s elderly community, and went on to earn his masters in Social Work from the University of Pennsylvania, where he also later worked to establish a curriculum around matters of aging and the elderly.

Finkle’s interest in photography wasn’t sparked until 1961 when he visited an exhibit by Harry Callahan at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He was inspired by Callahan and learned from his work, along with the works of W. Gene Smith, Andre Kerterz and Josef Koudelka. Following in their footsteps Finkle shoots predominantly in black and white film. However, it wouldn’t be until 1967 that he picked up a camera. This was around the time his children were born, and like any new parent, Finkle bought his first camera to ensure that no moment of his new family would be forgotten. Quickly, Finkle took a greater interest to photography and began snapping photos as a hobby. “I would walk the streets and just shoot what caught my eye” he said.

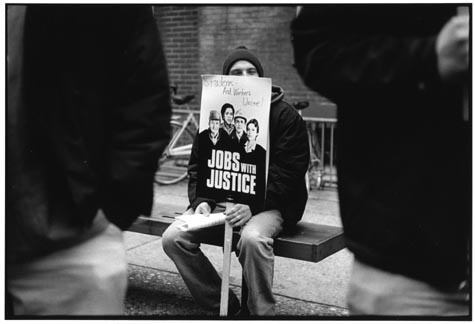

Year by year his interest grew, and by 1972 he had fully fallen in love with photography. His family photoshoots and street walking had transitioned into a full-time job as a freelance photographer and photojournalist. His career is too extensive to cover every moment, but he walked me through stories and moments that were influential to his work. His career covers a full spectrum of work. It includes long tenures with social movement organizations or outlets like the Philadelphia Public School Notebook, Juntos, Disabled in Action, Project Home and the New Sanctuary Movement, just to name a few. When these organizations held a protest or demonstration Finkle was their man there to captured it all. What was astonishing to me is Finkle’s generosity. When shooting for these organizations and those like it, he predominately shot free of charge. What’s most important for Finkle are the issues these people are fighting for.

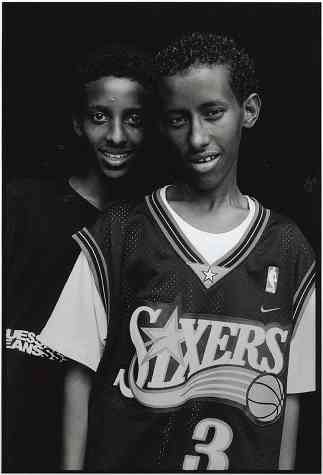

When not shooting for allied organizations Finkle seeks stories that he believes are important and deserves to be told. His projects mainly focus on people and circumstances that normally go unnoticed by mainstream media sources. Issues of poverty, labor rights and immigration. He has created numerous exhibits that have been shared across the United States and displayed to international audiences. Partnering with the Honickman Foundation and the Philadelphia Free Library Finkle created the Philadelphia Mosaic exhibit. With this project he followed ten immigrant families through Philadelphia to capture what routine life is like for them in a new land. As he followed these families from their children’s classrooms, to their dinner tables and to their areas of worship he’s able to show the nuances of life these families share not only with one another, but with the surrounding Philadelphia community.

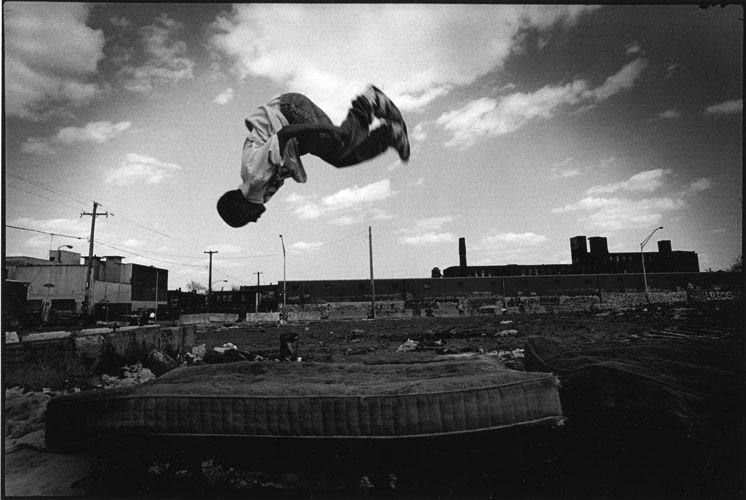

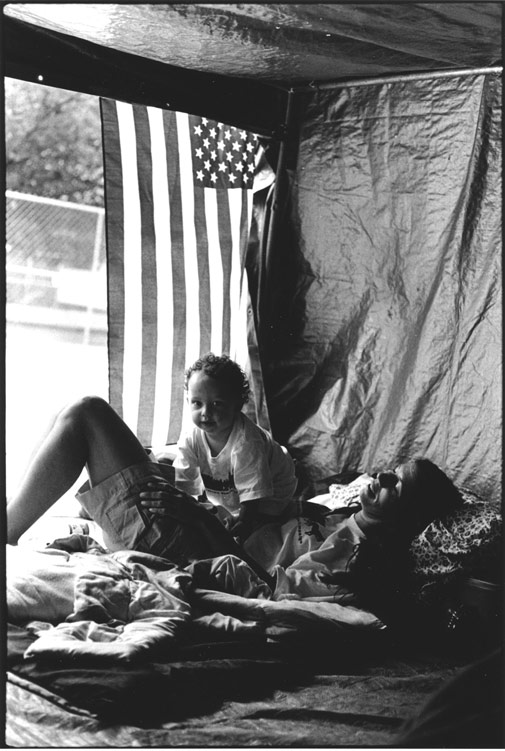

Finkle is able to find the reality of the subjects he’s shooting. For instance, the reality of poverty facing too many of our fellow citizens. Partnering with the William Penn foundation and the Kensington Welfare Rights Union, Finkle created Urban Nomads: A Poor People’s Movement – a project offering insight into the lives of Philadelphians living in extreme poverty and homelessness. His photographs tell the hidden narrative. When touring with this exhibit in Brazil Finkle recounted the astonishment on people’s faces. “They couldn’t believe that this sort of poverty existed in the United States” he said.

Finkle’s work also focuses on the history of Philadelphia. One of his most well-known projects is Still Home: The Jews of South Philadelphia. South Philadelphia was known for its many immigrant communities who settled there in the 19th and 20th centuries. What once was a sprawling community of over 200,000 Jewish people, had dwindled significantly by the turn on the millennium. With this project he captured the spirit of an aging but vibrant community and its contribution to the history of South Philadelphia.

Finkle’s collection of work is a time machine of the social, political and activist history of Philadelphia. For me, Finkle is not only a Photographer but is a historian. As we talked, he described moments in Philadelphia’s history that has shaped the wrought city into its existence today. One moment in particular was the 1967 Philadelphia School Board hearing, in which 3,000 mostly black students march upon the Board of Education building to demand curriculum and school policy changes. These brave students were met by riot officers wielding night sticks and police dogs, sent by orders of then police commissioner Frank Rizzo.

This powerful but unfortunate demonstration was significant for Finkle. Concerned citizens disgraced by the treatment of African American students in the classroom and the city’s violent response to their peaceful protest spawned the People for Human Rights movement in Philadelphia. From this movement, Finkle cofounded The People’s Fund, – a nonprofit organization whose mission is to raise money for grassroots organizations working for “racial equity and economic opportunity for all” – which today is known as Bread and Roses Community Fund.

His experiences in progressive movements offers a distinctive perspective on Philadelphia. I was intrigued in hearing his thoughts on the current state of the city. “Philly is a tale of two cities” he said. Everything has changed culturally for Philadelphia according to Finkle. The city is much more vibrant and active in many areas, but for many less fortunate people nothing has changed. “It hasn’t changed for those who are poor.”

Currently Finkle is working on archiving his work. A task that isn’t easy for someone with five decades worth of material. Once complete, people will be able to absorb work that offers a realism into the social struggle for equality, along with the hidden history of Philadelphia. I asked Finkle to offer a word of advice for aspiring photographers. With little hesitation he said, “Do it. Take out your camera and click it”. He urged photographers to pave their own path. “Find what’s important to you and tell that truth through your photographs.”